There has been a rush of enthusiasm to use Beransa in older dogs suffering from arthritic and other pain since it arrived here in NZ. It’s understandable when you hear stories of dogs moving more freely. But, as with any drug, there are pros and cons.

I would also add that just because your dog is more comfortable on Beransa (or any other pain management drug) does not mean that you should be taking them for long hikes in the hills. Why? Because that’s not age appropriate exercise and just because they can’t feel the pain doesn’t mean that they suddenly have young joints. There is still underlying wear and tear…

In this blog post, I share the blog of Dr Darryl Millis, who is a Diplomate of both the American College of Veterinary Surgeons and the American College of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation, and a Professor of Orthopedic Surgery and Director of the CARES Center for Veterinary Sports Medicine at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine. (Dr Millis created the Certified Canine Fitness Trainer qualification which I completed earlier this year).

What about Librela, Anti-Nerve Growth Factor Antibody Treatment?

Osteoarthritis affects approximately 50% of large breed adult dogs. It is therefore necessary to develop effective treatments to alleviate lameness, pain, and mobility disorders. Anti-nerve growth factor antibody treatment is a newly approved drug that has shown promising results.

But how effective is it, and how should it be used? These are critical questions because there is a certain amount of “hype” with any new drug that is purported to be an effective treatment for a difficult and common condition. Further, there is a tendency to use it freely for other conditions that it is not approved for. Is it safe for other conditions? We don’t know yet, but it is important to understand the mechanism of action to predict if there are concerns using it to treat other conditions.

What is Nerve Growth Factor?

Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) is a protein that plays a role in pain transmission, and elevated levels of NGF contribute to pain and inflammation in the joints. NGF also plays a crucial role in promoting the growth, maintenance, and survival of nerve cells (and this gives some clues regarding when NOT to use anti-NGF antibodies – see below). By blocking the action of NGF, anti-NGF antibodies can reduce pain signals from the joints, resulting in pain relief for dogs with arthritis.

What is Anti-Nerve Growth Factor Antibody?

Anti-NGF antibodies are genetically engineered proteins that specifically target and neutralize nerve growth factor. The concept behind anti-NGF antibody treatment is to block the action of nerve growth factor, thereby reducing the pain signals transmitted to the brain. By inhibiting the function of nerve growth factor, anti-NGF antibodies effectively alleviate arthritis symptoms in dogs. But how exactly do these antibodies work?

When administered by injection, anti-NGF antibodies bind to nerve growth factor molecules in the body, preventing them from binding to nerve cells and transmitting pain signals. By interrupting this process, anti-NGF antibodies offer a targeted approach to pain management in arthritic dogs.

Research studies have shown promising results regarding anti-NGF antibodies in treating arthritis in dogs. Treated dogs have shown some improvement in mobility and reduced pain.

What is Anti-Nerve Growth Factor Antibody Used for, and What is it Not Used For?

It’s important to note that anti-NGF antibody therapy should only be administered under the supervision of a veterinarian. Each dog’s condition and response to treatment may vary, which is why a professional assessment is crucial. Remember it is ONLY APPROVED FOR OSTEOARTHRITIS. It has not been approved for immune-mediated arthritis, such as Rheumatoid arthritis, or post-operative pain. Your veterinarian should evaluate factors such as your dog’s age, breed, medical history, and any pre-existing health conditions that could affect the treatment’s efficacy or safety. It should only be administered to dogs with confirmed osteoarthritis (radiographs and clinical diagnosis). A neurological evaluation should also be performed because the use of anti-NGF antibodies in dogs with spinal cord or nerve conditions may worsen the condition. It’s essential to discuss the potential benefits and risks associated with this treatment option with your veterinarian to make an informed decision for your pet.

Are There Any Side Effects or Precautions?

As with all drugs, there are potential side effects and limitations of anti-NGF antibody therapy. Common side effects may include allergic reactions (including anaphylactic shock – your dog should stay in the clinic for at least 20 minutes after the injection), injection-site reactions, and increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN – associated with kidney function). Severe adverse effects may be possible when it is administered inappropriately, which emphasizes the importance of close monitoring and regular check-ups during the treatment period. Until further studies are available, in my opinion, it should not be used in dogs with neurologic conditions or in dogs with unstable joints. It goes to reason that if a dog has a neurologic condition, such as degenerative myelopathy or intervertebral disk herniation, that NGF should NOT be inhibited. When there is damage to the spinal cord, you want nerve growth factor to help with healing the spinal cord and nerves. In addition to pain receptors in the joint, there are also nerves that sense changes in joint position. If there is joint instability, such as a cranial cruciate ligament rupture, joint position awareness or joint proprioception is important to allow correction of abnormal joint positions by muscle contraction to help protect the joint. Anti-NGF antibody may inhibit the function of these nerves, resulting in “sloppy motion” and cause arthritis to progress much faster. Experimentally, inhibition of joint position awareness may drastically increase the amount of arthritis that develops in an unstable joint. In fact, this may explain why this drug has not been approved in people, because some individuals receiving treatment develop rapidly progressive osteoarthritis. Moreover, as anti-nerve growth factor antibody treatment is a relatively new approach, long-term effects and safety concerns are still being studied. It is crucial to stay informed about the latest research and maintain open communication with your veterinarian regarding your dog’s response to the treatment.

How Well Does It Work?

It is important to note that the response to this treatment can vary among dogs. Some may experience significant relief, others may have a more gradual response, and many dogs may have no response. Patience is key during this process, and it is essential to maintain regular check-ups with your veterinarian to assess the effectiveness of the treatment.

There are several studies that have been published, but we will focus on the study performed in the US that was used for FDA approval because these are monitored very closely and the data are scrutinized by the investigators, the sponsoring company, and independent evaluators. They evaluated 135 dogs in the Librela group and 137 in the placebo group. Dogs were treated on days 0, 28 and 56, and were followed for 84 days. First, realize that there is a high placebo rate in studies of dogs with osteoarthritis. The dogs do not know if they have the active drug or a placebo, so why does this occur? First, osteoarthritis does not have a constant level of clinical signs – the signs wax and wanr. So, depending on what has happened the day before the evaluation, the clinical signs may be improved or worse when the dog is evaluated. Further, many outcome evaluations are subjective in nature (either the owner or veterinarian assesses lameness or pain by their observations), and as such, are prone to inaccurate assessments of pain or lameness severity, and there is a “caregiver effect”, meaning that we want the drug to work and may score the assessment more favorably. Objective outcome evaluations, such as measuring weight bearing with a force platform, are much better and do not “over-interpret” the assessment while giving an actual amount of force being placed on the lame limb. Unfortunately, the studies for approval only used subjective assessments.

The Canine Brief Pain Inventory was used in this study and has been used in other arthritis studies. It relies solely on owner assessment, with the following questions addressed using a 10-point scale.

Pain Severity

Fill in the oval next to the one number that best describes the pain at its worst in the last 7days.

Fill in the oval next to the one number that best describes the pain at its least in the last 7 days.

Fill in the oval next to the one number that best describes the pain at its average in the last 7 days.

Fill in the oval next to the one number that best describes the pain as it is right now.

Pain Interference

Fill in the oval next to the one number that best describes how during the last 7 days pain has interfered with your dog’s:

- General Activity

- Enjoyment of Life

- Ability to Rise to Standing from Lying Down

- Ability to Walk

- Ability to Run

- Ability to Climb Stairs, Curbs, Doorsteps, etc.

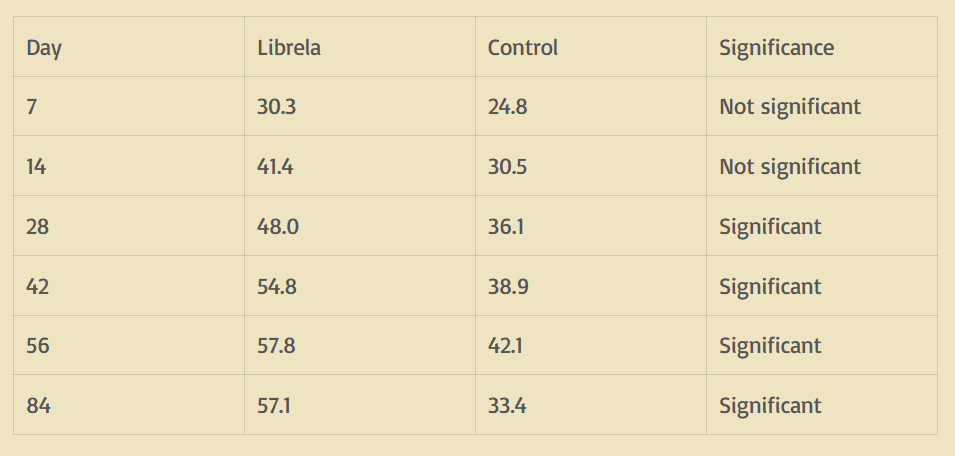

Treatment success was defined as a reduction of 1 or greater in the Pain Severity Score and 2 or greater in the Pain Interference Score vs. Day 0. So, in practical terms, an improvement of 1 out of 40 in the Pain Severity Score and 2 out of 60 in the Pain Interference Score. Not exactly earth-shattering improvement. They reported the percentage of dogs in each group that met the treatment success category as the main support of efficacy for FDA approval. The results are shown in the table below.

The results of a similar study done for approval in Europe showed results that were relatively the same, with the Librela group having a 50% success rate and the placebo group having a 24% success rate by day 84.

So what does this mean? If we look at day 28 when the treatment reached statistical significance over the placebo, 48 out of 100 dogs given Librela met the criteria for treatment success, while 36 of 100 dogs given the placebo met the criteria for treatment success. This means that Librela helped 12 more dogs out of 100 achieve mild improvement compared to the placebo. If we look at the day 84 time period (which was the biggest difference), 57/100 dogs given Librela improved, and 33/100 given placebo improved, meaning the drug helped 24/100 dogs.

Bottom Line?

The anti-NGF antibody took at least 1 month to work, and given for at least 3 months, the drug helped roughly half the dogs improve with treatment, while 1/3 of dogs receiving placebo improved using their criteria for treatment success. How does this stack up with other treatments? Other FDA studies that have evaluated nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (which generally have the most complete data) suggest that approximately 25-50% receiving a placebo show improvement in whatever criteria are being evaluated, while approximately 70-90% of dogs receiving an NSAID show improvement. Also, most dogs receiving an NSAID show improvement by 7 to 14 days after starting treatment. Our studies show approximately 70-75% of dogs receiving extracorporeal shockwave treatment improve, compared to 25% in the placebo group. So overall, it seems a bit difficult to get excited about a drug that helps fewer patients than most other treatments and takes at least a month to show improvement. Now, social media (for whatever that’s worth) suggests some dogs have improvement within 4-5 days. Similarly, some owners report severe side effects within that time frame, many related to weakness, near paralysis, and incontinence, with most of these presumably neurologic in origin. In a discussion with a company representative, they indicated that they were unaware of any neurologic signs after treatment. So there seems to be a disconnect on this issue. Some of the dogs with neurologic side effects may have had an underlying neurologic condition that may have been exacerbated with anti-NGF antibody treatment, emphasizing that dogs should be thoroughly evaluated and only receive treatment for osteoarthritis, and no other conditions that cause pain.

I’m often asked what I would do if it was my dog. Based on the current information regarding possible side effects and treatment effectiveness, I would only use it if my dog was already thin (not overweight), current pain management for osteoarthritis was no longer effective or liver or kidney disease was present rendering them unable to take NSAIDs, and had end stage osteoarthritis. My concerns are that other available treatments may be more effective, treatment of early osteoarthritis may result in reduction of joint position awareness, potentially increasing the progression of osteoarthritis, and there is the possibility of neurologic side effects.

Don’t Forget About Other Treatments for Osteoarthritis

Additionally, providing your dog with a comfortable and supportive environment is crucial. Maintaining a healthy weight for your dog is particularly important because excess weight can aggravate arthritis symptoms. Consider investing in orthopedic bedding or ramps to minimize stress on their joints and allow for easier mobility. Other treatments to provide a comprehensive approach to arthritis management include appropriate pain management, physical rehabilitation, and, when necessary, surgical interventions.

Source: MyLameDog.com