It’s a win for Darwin’s Dogs and open access data! A new study published in the journal Science Advances has identified genomic links to the behaviours of herding breeds. The study used data entirely sourced from open-access databases.

Researchers at Korea’s Gyeongsang National University and the U.S. National Institutes of Health analyzed data exclusively from publicly available repositories, including genomic and behavioral data from the community science initiative, Darwin’s Dogs. Their findings are powerful examples of how open science—making research data freely and publicly available—can accelerate discovery by helping scientists leverage existing data in innovative ways.

Herding breeds carry genes linked to cognitive function

Herding breeds like the Australian cattle dog, Belgian Malinois, and border collie have a long history of helping humans move and manage livestock. These dogs are renowned for their precise motor control, sharp intellect, and unwavering drive. In fact, motor patterns required for effective herding—like eyeing, stalking, and chasing animals without killing them—have been so deeply ingrained in herding dogs through generations of selective breeding that even non-working lines often display these traits. But while herding behaviors have been recognized and refined for centuries, their genetic roots have remained largely unknown.

To explore the genetic foundations of herding behaviors, researchers conducted a large-scale genomic comparison across dogs from 12 herding breeds and 91 nonherding breeds. They identified hundreds of genes that have been naturally selected in herding breeds, several of which, through additional analysis, they found linked to cognitive function.

Narrowing their focus to the border collie, a breed celebrated for its intelligence, the research team identified more than eight genes strongly associated with cognition. One of the standouts was EPHB1, a gene involved in spatial memory. Several variants of EPHB1 appeared across herding breed genomes, suggesting that this gene may support the array of complex motor patterns and decision-making skills essential for herding.

Darwin’s Dogs’ database connects genomic discoveries with behavioral insights

Identifying genes associated with breeds is one thing, but understanding their function is another. This is where Darwin’s Dogs’ open-access behavioral and genomic datasets became critical to expanding the impacts of the study’s findings.

Darwin’s Dogs invites dog owners to participate in scientific research by taking behavioral surveys about their dogs and contributing DNA samples for whole genome sequencing. As part of Darwin’s Ark’s open science commitment, this data is de-identified and made available to researchers around the world, creating a unique open-access resource that allows scientists to explore connections between canine DNA and behavioral traits.

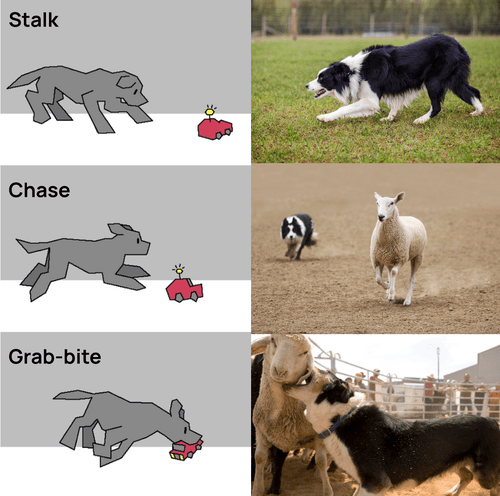

The researchers analyzed data from 2,155 dogs in the Darwin’s Dogs database to see whether dogs with the EPHB1 gene behaved differently than dogs without the gene. They found a strong link between EPHB1 and behavior: dogs with this gene were significantly more likely to show toy-oriented behaviors such as stalking, chasing, and grab-biting toys. These actions closely resemble motor patterns seen in herding behaviors.

This link held true even among dogs with mixed breed ancestry, and within border collies from working versus non-working lines, reinforcing the strong connection between EPHB1 and herding-related behaviors.

Open science opens doors to discovery

This study’s discoveries were made possible through open science. Data from open science initiatives like Darwin’s Dogs—and the thousands of community scientists who shared behavioral insights about their dogs—helped researchers connect genomic markers to observable behaviors. The scale and scope of the Darwin’s Dogs database helped the research team analyze behavioral associations to the EPHB1 gene across dogs with varied breed ancestry.

This research serves as a model for how professional researchers and community scientists can come together to accelerate scientific progress. When community scientists contribute to open repositories like Darwin’s Dogs, the possibilities for discovery are endless.

Resources

Read the paper published in Science Advances: Hankyeol Jeong et al. , Genomic evidence for behavioral adaptation of herding dogs. Sci. Adv. 11,eadp4591(2025).DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adp4591

Source: Darwin’s Ark blog